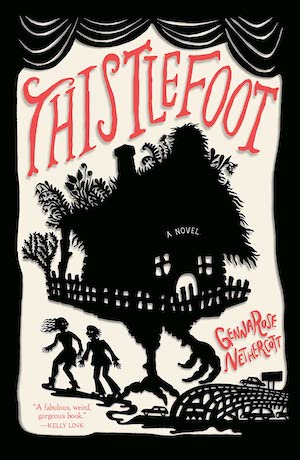

It’s a rare treat to find a book that moves so confidently through as many paces as GennaRose Nethercott’s Thistlefoot. There’s the rollicking, off-center lope of Isaac Yaga, who never stays in one place for long enough for anyone to recognize his true self, and the lonesome, cautious pace of Bellatine Yaga, his sister, whose hands hold an uncommon power that she would rather not use.

There’s the start-stop gait of the trio of musicians who travel in a school bus, and the stately forward momentum of Winifred, the girl who used to be stone. There’s the implacable, unhurried horror-movie stride of the Longshadow Man. And there’s the merry and marvelous footsteps of Thistlefoot itself—the house on chicken legs that occasionally gets to tell its own parts of this tale.

And what a tale it is: one of puppetry, magic, metamorphosis, loss, memory, witnessing, hungry ghosts, and gleaming lanterns. It’s a story that crosses oceans and generations, and finds, in the skills and hearts of its characters, the vital memories and stories of those long gone.

Thistlefoot begins when Bellatine and Isaac Yaga come into a strange inheritance. Their twice-great grandmother leaves them something so large, they have to pick it up in a Red Hook warehouse. The Yaga siblings haven’t seen each other for years, but they are both exactly how they expect each other to be—and out of their depth when it comes to their ancestor’s gift.

Buy the Book

Thistlefoot

Thistlefoot is a house; Thistlefoot is a mode of transportation; Thistlefoot is a character; and Thistlefoot is yet more things, which Nethercott carefully reveals. (“If you try to make me sit still, I’ll kill you,” the house says the first time it takes over the narrative. I fell in love with it at this precise moment.) Thistlefoot came into being when it was the home of Baba Yaga, but this is Nethercott’s own version of the legendary witch of Slavic folklore—not an intimidating crone, but a Jewish mother in an Eastern European shtetl who experiences a grief “so furious it has pushed God aside and become its own god.”

Bellatine feels like Thistlefoot is home, but Isaac sees another opportunity, a way to keep moving and to make money. He proposes a deal: They will pick up the family puppet-show business, and after a tour, he gets all the money—and she gets the house. Tiny, as Isaac calls his sister, will not touch the puppets. He will be Strings, in charge of the characters. She will be Rigs, handling everything else. It’s a perfectly good plan.

Or it would be, were there not a nightmare creature on their tail. The Longshadow Man, as we learn this eerie manipulator is called, won’t rest until he catches up to Thistlefoot. With a bottle of vicious spirits and an earful of lies, he lures people to his cause, which is—to put it simply and purposefully vaguely—destruction.

The Longshadow Man destroys a lot, in this story, and it’s hard to watch, hard to see the way he goes for the lonely, the isolated, the young and posturing, the marginalized and talented. What he most wants to destroy, though, is bigger than a person, bigger than even a house. It’s a memory. He wants to control how a story is told, and who figures in it, and who survives.

Early in Thistlefoot, Nethercott beautifully shows us her hand:

“And the very worst thing about memory, the deadliest, most brutal part: memory can be forgotten.

“But a folktale—a folktale can never be forgotten because it wriggles and rearranges until it sits neatly on the heart. It is fluid and changing, able to adapt to whatever setting it finds itself in. It shifts in the mouth of every teller and adapts to the shape of each listener’s ear. The facts can change (place names, the color of a character’s woolen coat, the particular flowers in a small, circular garden), but the core remains the same. So, the folktale survives. Assimilates. And with it—so survives the memory.”

At this point, her story has yet to reveal itself, though her focus on memory and story is clear. But with every step taken—whether by a Yaga; by Isaac’s mysterious and wonderful cat, Hubcap; by Thistlefoot or by one of the siblings’ unexpected allies—Nethercott builds an incredible sense of momentum. For a while, you have to trust what she’s doing with that momentum, with this story of prickly women in skull-patched jackets and slippery men who turn into exactly who you don’t want them to be. You have to have patience with the ways that Issac and Tiny both avoid the story that needs to be told: They’re avoiding something big and heavy and beautiful and horrible, something they don’t even know is in their blood.

But the chickens—or the chicken-legged—will always come home to roost.

For pages, chapters, great swaths of Thistlefoot, I was not exactly sure where Nethercott was going, but I was happy to be along for the ride. Then, the truths start to creep in. The observations about the hungry ghosts of America, the pain that came here via so many modes of transportation, the things remembered and the things people would rather forget. The way she doles out the story of Baba Yaga, back in Gedenkrovka (a fictional town based on a real one), where a very human darkness starts to creep in around the edges.

And then, in the back end of this book, Nethercott’s set snaps fully into place, a piece of magical stagecraft rendered in book form.

“Generations pass, and suddenly, we forget. Our descendants are born yearning and they do not know why, for they have forgotten. Their hands are full of fire. Their legs are trembling to flee. The body remembers. The soured air remembers. We cannot forget. I cannot forget. And if I am to remember, so too, I vow, will you.”

Thistlefoot is an act of memory that takes the shape of a house and the shape of a book. It’s also the shape of two siblings who are the end of a line of people who have remembered things so long, and so hard, that these things are literally in Isaac and Bellatine’s bodies: transformation, fire, witnessing. It’s a story about stories in the best way: a story about how stories keep culture, keep memories, keep beliefs and ways of life alive. On both a deeper and a more intimate scale than Neil Gaiman did in American Gods, Nethercott brings a folktale to this country and sets it loose on the road, looking to understand who believes in it, and how, and why that matters.

Thistlefoot is published by Anchor.

Read an excerpt here.

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.